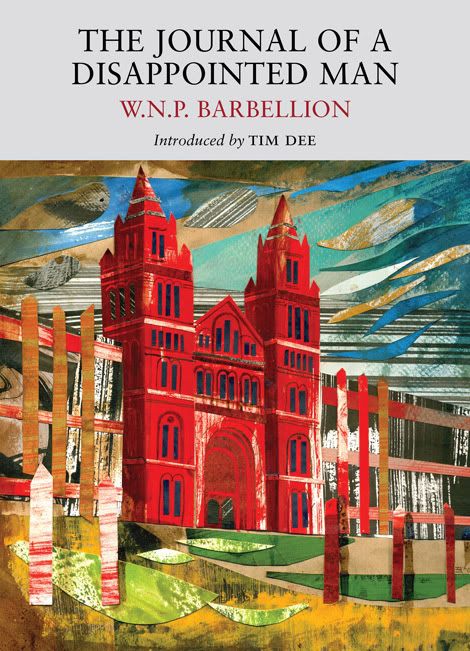

This week I read The Journal of a Disappointed Man by W.N.P. Barbellion, my third book for 52 Books in 52 Weeks. The Journal was recently re-published by Little Toller Books in the UK and is also available in the public domain via Google Books and the Internet Archive. It has been called a "masterpiece of personal observation," likened to the work of writers such as Franz Kafka and James Joyce, and was described by Ronald Blythe as "among the most moving diaries ever created."

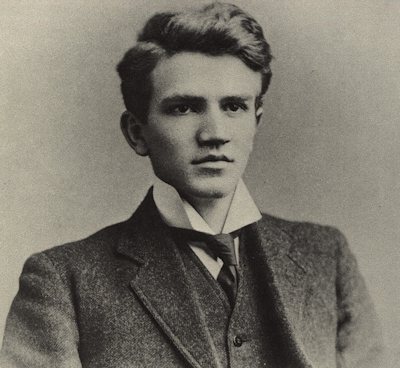

W.N.P. Barbellion was the nom-de-plume of Bruce Frederick Cummings (7 September 1889 - 22 October 1919). The initials W.N.P. stood for Wilhelm Nero Pilate, whom the author thought to be the most despicable people in history (Wilhelm being Kaiser Wilhelm the II since the diaries were published during the First World War). Barbellion was a name above a shop in South Kensington that Cummings passed every day.

The Journal begins in 1903 when the author is 13 years old. His brother would later recall:

"He read all kinds of books, from Kingsley to Carlyle, with an insatiable appetite. It was about this time, too, that he began those long tramps into the countryside, over the hills to watch the staghounds meet, and along the broad river marshes, that provided the beginnings and the foundation of the diary habit, which became in time the very breath of his inner life.

In these early years, I remember, the diary took the outward form of an old exercise book, neatly labelled and numbered, and it reflected all his observations on nature. The records, some of which were reproduced from time to time in The Zoologist, were valuable not only in their careful exactitude, but for their breadth of suggestion, and that inquiring spirit into the why of things which proved him to be no mere classifier or reporter. They were the outcome of long vigils of concentrated watching."

He taught himself how to dissect, and afterwards his patient and unerring skill surprised his examiners. "Scientists and naturalists of repute--reading his published records of observations--called upon him and were puzzled to find him a mere boy." By the time he was fourteen, "his fixed determination to become a naturalist by profession was accepted by all of us as a settled thing." (A.J. Cummings, A Last Diary)

Despite being almost entirely self-taught, in October 1911 he placed first in an examination for a position at the British Museum of Natural History in London, and in January 1912 commenced an assistantship there.

Bruce Frederick Cummings c. approx. 1910

"For an unusually long time after I grew up, I maintained a beautiful confidence in the goodness of mankind. Rumours did reach me, but I brushed them aside as slanders. I was an ingénu, unsuspecting, credulous." (The Journal of a Disappointed Man)

Gradually, as his ambitions began to change, his writing evolved from the dry scientific notes of the earlier Journal into something more personal and literary (and hence, imminently more readable!).

"He wrote down instinctively and by habit his inmost thoughts, his lightest impression of the doings of the day, a careless jest that amused him, an irritating encounter with a foolish or a stupid person, something newly seen in the structure of a bird's wing, a sunset effect. It was only on rare occasions that he deliberately experimented with forms of expression." (A.J. Cummings, A Last Diary)

There is an element of despair throughout the Journal as he struggled with chronic ill-health (and a fair amount of hyperchondria), and also occasional bouts of depression. "Chronically sub-normal" was how he once described his condition to his brother. In London, he grew slowly and steadily worse and, upon the advice of his brother saw a "first-class nerve specialist" who promptly diagnosed him with what we now call multiple sclerosis. Yet the decision was made not to tell him the true nature of his illness, so as not to precipitate his demise.

In October of 1914, he discovered the Journal of the Russian painter Marie Bashkirtseff (1858–1884). “I am simply astounded," he writes. “It would be difficult in all the world’s history to discover any two persons with temperaments so alike. She is the ‘very spit of me’!” This seems to have inspired his decision, in December of that year, to "prepare and publish a volume of this Journal."

The diaries, up through the winter of 1917 were eventually published in March 1919 and the book was an immediate sensation (though many believed it was a work of fiction, written by H.G. Wells who had written book's preface). A later journal entitled A Last Diary was published after his death in 1919, as well as a book of essays, Enjoying Life and Other Literary Remains.

"I do not think that there can be two minds about the great literary qualities and the poignant interest of his one tragic work. It is a book that is continually sought and steadily reprinted – the story of a soul in the grip of the obscure and pitiless arterial [sic] disease that finally killed him, resolved to find expression and a use for itself in the ever darkening shadow of death. 'Barbellion’s Diary' I am convinced will still be read with interest, curiosity and sympathy, when most of the larger more fluid successes of to-day have passed out of attention." (H. G. Wells, letter to Barbellion’s widow, 8 September 1925, Source)

"For as long as his remarkable journal is published he will live with it, his constrained existence celebrated for the courage that so brightly distinguishes it." (William Trevor, “On the Shelf”, Sunday Times, 5 November 1995, Source)

"To me the honour is sufficient of belonging to the universe — such a great universe, and so grand a scheme of things. Not even Death can rob me of that honour. For nothing can alter the fact that I have lived; I have been I, if for ever so short a time. And when I am dead, the matter which composes my body is indestructible—and eternal, so that come what may to my 'Soul,' my dust will always be going on, each separate atom of me playing its separate part — I shall still have some sort of a finger in the pie. When I am dead, you can boil me, burn me, drown me, scatter me — but you cannot destroy me: my little atoms would merely deride such heavy vengeance. Death can do no more than kill you." (The Journal of a Disappointed Man)

Boat on the River Taw, Barnstaple, Devon © dotjay

Labels: Kindle, Nook, Reading, World History, WWI

0 Comments:

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)